Why Stress Relief Isn’t Working for You—And What Actually Helps

Stress is more than just feeling overwhelmed—it’s a silent driver behind many preventable health issues. I used to think checking off tasks and drinking green tea was enough, but my body said otherwise. After months of burnout, sleepless nights, and constant fatigue, I realized I’d been falling into the same traps most people do. This isn’t about quick fixes. It’s about rethinking how we truly release stress—before it leads to something worse. Let’s break down what really works.

The Hidden Cost of Ignoring Daily Stress

Chronic stress is not simply a matter of feeling anxious or overburdened. It is a physiological condition that persists even when external pressures seem minor. Unlike acute stress, which triggers a temporary surge of adrenaline to help you respond to immediate threats, chronic stress keeps the body in a prolonged state of alert. This continuous activation affects multiple systems: the immune response weakens, digestion slows or becomes erratic, and cardiovascular strain increases. Over time, these changes contribute to long-term health complications, including high blood pressure, type 2 diabetes, and autoimmune conditions.

Many people assume they are managing stress because they don’t feel emotionally overwhelmed. However, low-grade, persistent stress can be deceptive. It operates beneath awareness, wearing down the body’s resilience without triggering obvious alarm signals. This kind of stress often goes unnoticed until symptoms become difficult to ignore. The danger lies in its invisibility—by the time health declines, the damage may already be significant. Research consistently shows that prolonged exposure to stress hormones like cortisol leads to increased systemic inflammation, a key factor in the development of many chronic diseases.

Common signs of unmanaged stress are frequently dismissed as normal parts of busy life. Irritability, difficulty concentrating, mild insomnia, and frequent colds are often chalked up to aging or overwork. Yet these are early warnings that the body is struggling to maintain balance. A person might feel they are “functioning fine,” but recurring headaches, muscle tension, or digestive discomfort suggest otherwise. Even subtle shifts—like reaching for snacks more often or feeling emotionally flat—can reflect the body’s attempt to cope with ongoing strain.

The long-term risks associated with chronic stress are supported by decades of medical research. The American Psychological Association and the National Institutes of Health both recognize stress as a contributing factor in heart disease, obesity, and mental health disorders. When the body remains in a state of high alert, it prioritizes survival over maintenance, meaning repair processes like cell regeneration and immune surveillance are downgraded. Over time, this imbalance increases vulnerability to illness. Understanding stress not just as an emotional experience but as a biological burden is the first step toward effective management.

Why Common Stress “Solutions” Fall Short

Most attempts at stress relief focus on temporary distractions rather than addressing the root cause. Activities like scrolling through social media, binge-watching television, or oversleeping on weekends are often marketed as forms of self-care. While they may offer brief relief, they rarely contribute to lasting calm. In fact, many of these habits can exacerbate stress by disrupting natural rhythms. For example, late-night screen use suppresses melatonin production, making it harder to fall asleep and reducing sleep quality. Poor sleep, in turn, heightens sensitivity to stress the following day, creating a self-reinforcing cycle.

Another limitation of popular stress management tools is their reliance on short-term interventions. Many people download meditation apps and try a five-minute session during lunch, hoping for immediate results. While mindfulness practices have proven benefits, their effectiveness depends on consistency and integration into daily life. A single session does little to recalibrate a nervous system that has been in overdrive for months. Without regular practice, the brain does not learn to shift out of survival mode, and the benefits remain superficial. True nervous system regulation requires repetition, not novelty.

There is also a widespread misconception about what self-care truly means. In popular culture, self-care is often portrayed as indulgent—a bubble bath, a shopping spree, or a weekend getaway. While these experiences can be enjoyable, they do not address the underlying patterns that lead to chronic stress. Real self-care is not about luxury; it is about consistency. It means establishing routines that support long-term well-being, even when they are not exciting or glamorous. Brushing your teeth is not a treat—it is a necessary habit. Similarly, stress management should be viewed as part of daily hygiene, not an occasional reward.

Perhaps the most significant flaw in common stress relief strategies is their dependence on external fixes. People often look for solutions outside themselves: a new app, a supplement, or a retreat. While these tools can be helpful, they are not substitutes for internal regulation. Lasting stress reduction comes from learning how to self-soothe, recognize early warning signs, and respond with intention rather than reaction. Relying solely on external aids can create a false sense of control, leaving individuals unprepared when those tools are unavailable. True resilience is built from within, through awareness and practice.

The Myth of “Just Relaxing”

Many believe that rest alone is enough to counteract stress. However, not all rest is created equal. Passive rest—such as lying on the couch or zoning out in front of the television—does not necessarily allow the nervous system to recover. In fact, if the mind remains active with worries or the environment is overstimulating, the body may stay in a state of low-grade alertness. True recovery requires active engagement in practices that signal safety to the brain. This shift from fight-or-flight to rest-and-digest mode is essential for healing and restoration.

The autonomic nervous system operates like a dial, not a switch. It cannot instantly shift from high alert to deep calm without guidance. Small, repeated signals are needed to convince the body that it is safe. This is where intentional practices come in. Techniques such as slow breathing, gentle movement, or listening to calming sounds help down-regulate the nervous system over time. Without these deliberate inputs, the body may remain stuck in survival mode, even during periods of apparent inactivity. The goal is not to eliminate stress entirely—that is neither possible nor desirable—but to restore balance after stress occurs.

A helpful metaphor is to think of the body as an instrument that needs daily tuning. Just as a piano goes out of tune with regular use, the nervous system drifts out of alignment when exposed to constant demands. Modern life presents unique challenges to this balance. Artificial lighting, especially blue light from screens, disrupts circadian rhythms. Constant notifications keep the brain in a state of vigilance. Sedentary work environments reduce opportunities for physical release. All of these factors interfere with the body’s natural ability to reset and recover. Recognizing these disruptions is the first step in creating countermeasures.

Active recovery involves creating conditions that support regulation. This includes exposure to natural light during the day, limiting screen time in the evening, and incorporating brief moments of mindfulness throughout the day. Even small changes—like stepping outside for fresh air or pausing to take three deep breaths—can serve as reset points. The key is consistency. Over time, these micro-moments accumulate, helping the nervous system relearn how to return to baseline. Relaxation is not a passive state to be achieved; it is a skill to be cultivated.

What Actually Works: Small, Science-Backed Shifts

Effective stress management does not require dramatic lifestyle changes. Research shows that small, consistent actions yield better long-term results than intensive but infrequent efforts. Three evidence-based practices stand out for their accessibility and impact: mindful breathing, nature exposure, and structured wind-down routines. Each of these helps regulate the nervous system in a gentle, sustainable way. The emphasis is not on duration but on regularity—five minutes a day is more effective than one hour once a week.

One of the most powerful tools is the 4-7-8 breathing technique. This method involves inhaling quietly through the nose for four seconds, holding the breath for seven seconds, and exhaling slowly through the mouth for eight seconds. Repeating this cycle four times activates the parasympathetic nervous system, which promotes relaxation. Studies have shown that controlled breathing can reduce heart rate, lower blood pressure, and improve sleep quality. The beauty of this practice is its simplicity—it can be done anywhere, at any time, without special equipment. It serves as an immediate signal to the brain that danger has passed.

Spending time in nature, even in urban green spaces, has been shown to reduce cortisol levels and improve mood. The concept of “forest bathing,” or shinrin-yoku, originated in Japan and is now supported by scientific research. Simply walking in a park, sitting under a tree, or tending to houseplants can provide measurable benefits. Natural environments engage the senses in a gentle, non-demanding way, allowing the mind to rest from constant cognitive processing. Even brief exposure—10 to 20 minutes a day—can enhance feelings of calm and mental clarity.

Equally important is establishing a structured wind-down routine in the evening. The brain responds well to predictable cues that signal the transition from activity to rest. Dimming the lights, turning off screens, and engaging in a quiet activity like reading or light stretching can prepare the body for sleep. Using consistent auditory or olfactory cues—such as soft music or a specific scent—can reinforce this routine over time. These habits are not about perfection; they are about creating a reliable pattern that supports recovery. When practiced regularly, they become automatic, reducing the mental effort required to relax.

Building Your Personal Stress-Release System

Since stress affects everyone differently, a personalized approach is more effective than a one-size-fits-all solution. The first step is developing self-awareness. This involves identifying personal stress triggers—situations, thoughts, or environments that consistently lead to tension. For some, it may be work deadlines; for others, family responsibilities or financial concerns. Equally important is recognizing how stress manifests physically and emotionally. Does it show up as shoulder tension, stomach discomfort, irritability, or fatigue? Mapping these patterns provides valuable insight into when and how to intervene.

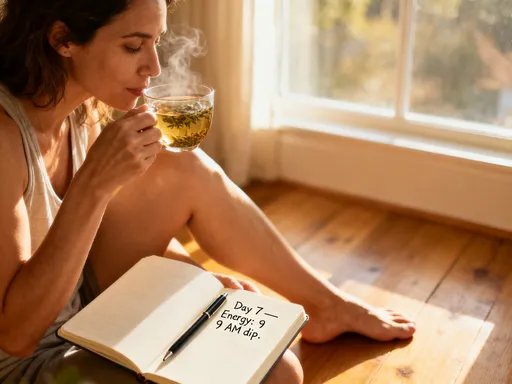

A practical way to build this awareness is to track mood and energy levels for one week. Using a simple journal or app, note how you feel at different times of day and what preceded those feelings. Over time, patterns will emerge—perhaps energy dips after meals, or irritability increases during evening commutes. This data helps identify high-risk periods and informs targeted strategies. For example, if stress peaks in the late afternoon, scheduling a short walk or breathing exercise at that time can prevent escalation.

Once patterns are understood, interventions can be matched to lifestyle. A desk worker might benefit from micro-breaks involving stretching or deep breathing every hour. A shift worker, whose schedule disrupts natural rhythms, may need stronger light cues and a consistent sleep routine regardless of shift timing. The key is to choose practices that fit seamlessly into existing routines. If a habit feels like a burden, it is less likely to be sustained. Small, manageable steps are more effective than ambitious but unrealistic goals.

Self-awareness also includes recognizing emotional responses. Some people tend to internalize stress, becoming withdrawn or numb, while others react outwardly with frustration or impatience. Understanding one’s typical response allows for early intervention. For instance, someone who notices they start clenching their jaw can use that as a cue to pause and reset. Over time, these moments of awareness become opportunities to practice regulation, turning stress signals into reminders for self-care.

When to Seek Professional Support

While self-directed strategies are valuable, they are not a substitute for professional care when needed. Persistent anxiety, unexplained physical symptoms, or emotional numbness may indicate that stress has progressed beyond manageable levels. These signs should not be ignored or minimized. Consulting a healthcare provider is a responsible and proactive step, not a sign of failure. A doctor can rule out underlying medical conditions and recommend appropriate support, such as counseling or therapy.

Mental health professionals, including psychologists and licensed counselors, are trained to help individuals develop coping strategies and process chronic stress. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), for example, has been shown to be effective in managing stress-related thoughts and behaviors. Medication may be considered in some cases, particularly when anxiety or depression is present. The goal is not to eliminate all discomfort but to restore balance and improve quality of life.

Preventive healthcare includes emotional and mental well-being, not just physical exams and screenings. Just as routine check-ups help catch physical issues early, addressing emotional health before crisis occurs leads to better long-term outcomes. There should be no stigma in seeking help—doing so reflects strength and self-responsibility. Professional guidance complements daily habits, providing tools and insights that enhance personal efforts.

It is also important to recognize when stress is linked to broader life circumstances, such as caregiving responsibilities, financial strain, or major transitions. In these cases, support systems—whether through community resources, support groups, or trusted friends—can make a meaningful difference. No one should have to navigate chronic stress alone. Accessing help is not a sign of weakness; it is an act of care.

Making Prevention a Lifestyle, Not a Chore

Stress management should not be reserved for moments of crisis. Instead, it is most effective when integrated into daily life as a form of ongoing maintenance. Reframing it as an act of self-respect shifts the motivation from avoidance to care. Just as brushing your teeth prevents cavities, daily stress-release practices protect long-term health. There is no drama in it—just quiet, consistent attention to what sustains well-being.

Over time, these small actions accumulate. Better sleep, improved focus, and stronger immunity are natural byproducts of a regulated nervous system. Emotional resilience grows, making it easier to navigate challenges without becoming overwhelmed. Relationships improve when irritability and reactivity decrease. The benefits extend beyond the individual, positively influencing family and community.

The goal is not to eliminate stress—some level of stress is normal and even necessary for growth. The aim is to build the capacity to recover. This requires a shift in mindset: from reacting to stress after it has taken hold to proactively creating conditions for balance. Daily practices are not about achieving perfection but about showing up consistently, even in small ways.

By treating stress management as a lifelong commitment, rather than a temporary fix, it becomes a natural part of living well. It is not about adding more to an already full schedule, but about weaving care into what is already being done. A few breaths before answering a call, a moment of stillness while waiting in line, a walk after dinner—these are not luxuries. They are essential acts of preservation. In a world that never stops demanding, choosing to pause is one of the most powerful choices you can make.