Why I Take Charge of My Health Before Illness Strikes

Have you ever waited until you felt sick to think about your health? I used to. But after learning how small daily choices shape long-term well-being, I shifted my mindset. Disease prevention isn’t just for doctors—it’s a personal commitment. This is how science helped me build habits that work, not when I’m broken, but while I’m still strong. Over time, I realized that waiting for symptoms is like waiting for a house to catch fire before installing smoke detectors. The body sends signals long before disease becomes visible, and modern medicine shows us that many chronic conditions are not inevitable—they are preventable. Taking charge early doesn’t require drastic measures, only consistent, informed choices grounded in science and self-awareness.

The Wake-Up Call: When Awareness Became Action

For many, the journey toward preventive health begins with a moment of clarity—often prompted by something ordinary, yet deeply personal. For one woman in her early forties, it was a routine blood test that revealed elevated blood sugar levels, despite feeling perfectly fine. She had no symptoms, no pain, yet the numbers told a different story. Another woman recalls her mother’s diagnosis with heart disease at age fifty-two, a wake-up call that made her confront her own family history and sedentary lifestyle. These experiences are not rare. They reflect a widespread pattern: most people do not consider their health until a doctor delivers news they weren’t prepared to hear.

This reactive mindset—that health only matters when illness strikes—is one of the greatest barriers to long-term wellness. Many believe that as long as they feel energetic and pain-free, their body must be functioning well. But scientific evidence shows otherwise. Conditions like hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and certain cancers can develop silently over years, causing internal damage before any noticeable symptoms appear. By the time discomfort arises, the disease may already be advanced. This delayed response often leads to more complex treatments, higher medical costs, and reduced quality of life.

The shift from reaction to prevention starts with awareness. It means recognizing that health is not merely the absence of disease, but a dynamic state influenced by daily behaviors. Research from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) indicates that up to 80% of heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes cases, along with 40% of cancers, could be prevented through lifestyle changes. These findings underscore a powerful truth: individuals hold significant influence over their future health outcomes. The decision to act before symptoms emerge is not driven by fear, but by empowerment—the understanding that small, consistent choices today can prevent major health challenges tomorrow.

What Disease Prevention Really Means (And What It Doesn’t)

Disease prevention is often misunderstood. Some assume it means avoiding all illness entirely, which is neither realistic nor accurate. Others associate it only with vaccinations or annual check-ups, missing the broader picture. In reality, disease prevention refers to a set of strategies aimed at reducing the risk of developing illness before it occurs. It is not about achieving perfection, but about increasing resilience and lowering vulnerability through informed actions. Public health experts categorize prevention into three levels: primary, secondary, and tertiary—each serving a distinct role in maintaining well-being.

Primary prevention focuses on stopping disease before it starts. This includes behaviors such as maintaining a balanced diet, staying physically active, avoiding tobacco, and getting recommended vaccines. For example, choosing whole grains over refined carbohydrates helps regulate blood sugar and reduces the likelihood of insulin resistance, a precursor to type 2 diabetes. Similarly, wearing sunscreen daily lowers the risk of skin cancer caused by UV exposure. These actions are proactive and accessible, requiring no medical intervention but yielding significant long-term benefits.

Secondary prevention involves early detection through screenings and regular monitoring. The goal here is to identify disease in its earliest, most treatable stages. Mammograms for breast cancer, colonoscopies for colorectal cancer, and routine blood pressure checks fall under this category. These tools do not prevent disease directly, but they allow for timely intervention that can halt or reverse progression. A person with high cholesterol may feel completely healthy, yet lowering those levels through diet, exercise, or medication can prevent a future heart attack.

Tertiary prevention comes into play after a disease has been diagnosed. Its purpose is to reduce complications and improve quality of life—for instance, cardiac rehabilitation after a heart attack or managing blood glucose levels in someone with diabetes. While important, tertiary prevention is not the focus of this discussion. The emphasis here is on primary and secondary strategies—those that preserve health before irreversible damage occurs. Crucially, disease prevention does not promise immunity. Genetics, environment, and chance still play roles. However, evidence consistently shows that preventive behaviors significantly reduce risk, extend healthy life expectancy, and enhance overall vitality.

The Science Behind Small Habits: How Daily Choices Add Up

It’s easy to underestimate the impact of daily routines—what we eat, how we move, when we sleep. Yet decades of research confirm that these seemingly minor decisions collectively shape our long-term health trajectory. Chronic diseases such as heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes are not sudden occurrences; they develop gradually, often rooted in years of lifestyle patterns. The American Heart Association emphasizes that up to 90% of cardiovascular disease could be attributed to modifiable risk factors, including poor diet, physical inactivity, and chronic stress. This means the majority of heart-related illnesses are not predetermined by genes, but influenced by behavior.

Consider the role of nutrition. Every meal sends biochemical signals to the body. A diet rich in processed foods, added sugars, and unhealthy fats promotes inflammation, insulin resistance, and arterial plaque buildup. In contrast, a pattern of eating centered on vegetables, fruits, whole grains, lean proteins, and healthy fats supports metabolic balance and cellular repair. Studies published in The Lancet have shown that improving dietary quality can reduce the risk of premature death by up to 20%. These benefits accumulate over time—much like compound interest in a savings account. Just as small deposits grow into substantial wealth, consistent healthy eating builds physiological resilience.

Physical activity operates on a similar principle. The human body evolved to move, and prolonged inactivity disrupts normal function. Regular movement improves circulation, enhances insulin sensitivity, strengthens the heart muscle, and supports mental health by regulating mood-related neurotransmitters. Even moderate exercise—such as brisk walking for 30 minutes five times a week—has been linked to a 35% lower risk of coronary heart disease. The key is consistency, not intensity. A person who walks daily may not see dramatic changes overnight, but over months and years, their cardiovascular system becomes more efficient, their joints more flexible, and their energy levels more stable.

Sleep is another foundational pillar. During rest, the body performs essential maintenance: repairing tissues, clearing brain toxins, and balancing hormones that regulate hunger and stress. Chronic sleep deprivation has been associated with increased risks of obesity, depression, and weakened immunity. The National Sleep Foundation recommends 7–9 hours per night for adults, yet nearly one-third of Americans report getting less than seven. Prioritizing sleep is not a luxury—it is a biological necessity. Think of the body as a garden: without regular watering, weeding, and sunlight, even the strongest plants will wither. Daily habits are the tools that nurture this internal ecosystem, ensuring it thrives rather than merely survives.

Mindset Matters: Building Health Consciousness in Everyday Life

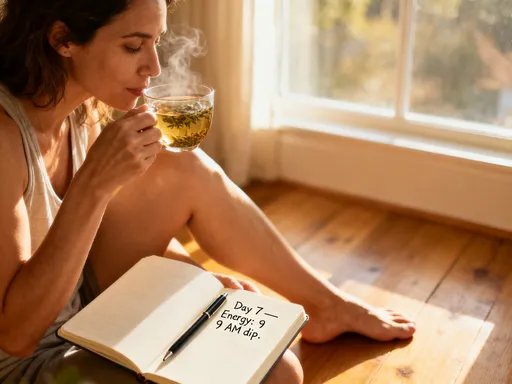

Beyond physical behaviors, a crucial element of preventive health is mindset—specifically, health consciousness. This refers to the ongoing awareness of one’s physical and emotional state, and the intentionality behind choices that affect well-being. A person with high health consciousness notices subtle shifts: a drop in energy after certain meals, changes in mood during stressful periods, or differences in sleep quality based on evening routines. These observations, when acknowledged and acted upon, serve as early warning systems, guiding adjustments before larger problems arise.

This level of awareness does not require constant self-monitoring or anxiety. Instead, it involves cultivating a gentle attentiveness—like checking the weather before planning an outdoor activity. Just as you might adjust your clothing based on temperature, you can adapt your habits based on how your body feels. For example, recognizing that skipping breakfast leads to afternoon fatigue might prompt a shift toward a more balanced morning routine. Noticing that screen time before bed disrupts sleep could inspire a digital curfew. These insights emerge not from obsession, but from curiosity and care.

Practical tools can support this mindset. Journaling, for instance, allows individuals to track patterns over time. Writing down meals, energy levels, or stress triggers can reveal connections that might otherwise go unnoticed. Some find value in weekly self-check-ins—asking simple questions like “How am I sleeping?” or “Do I feel physically strong this week?” These reflections create space for intentional decision-making, rather than defaulting to habit or convenience. Over time, this practice fosters a deeper relationship with one’s body, built on trust and responsiveness.

Health consciousness also involves rejecting the all-or-nothing mentality. Many people abandon healthy habits because they believe progress requires perfection. But science supports a different model: sustainable change comes from small, repeatable actions. Missing a workout or eating dessert does not negate weeks of effort. What matters is the overall pattern. By shifting focus from extreme goals to daily consistency, individuals build resilience against setbacks and maintain motivation over the long term. This mindset transforms health from a chore into a form of self-respect—an ongoing conversation between body and mind.

Actionable Steps Backed by Science: What Actually Works

Knowledge is valuable, but action creates change. Among the many health recommendations available, three core practices stand out for their strong scientific support and broad accessibility: regular physical activity, balanced eating patterns, and effective stress regulation. These are not extreme or time-consuming regimens, but realistic habits that can be integrated into everyday life, regardless of age, schedule, or fitness level.

Physical activity is one of the most powerful preventive tools available. The “why” lies in its systemic benefits: it improves cardiovascular function, enhances insulin sensitivity, reduces inflammation, and supports brain health. The “what” is simple—aim for at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity per week, as recommended by the World Health Organization. This can include brisk walking, cycling, swimming, or even active housework. Strength training twice a week further protects bone density and muscle mass, which naturally decline with age. The “how” involves making movement convenient: taking the stairs, parking farther away, scheduling short walks after meals, or following online exercise videos at home. The goal is not to train for a marathon, but to stay consistently active.

Balanced eating is equally important. The “why” centers on nutrition’s role in fueling cells, regulating metabolism, and preventing chronic disease. Rather than focusing on restrictive diets, the “what” should emphasize variety, moderation, and whole foods. A plate that includes vegetables, lean protein, whole grains, and healthy fats provides sustained energy and essential nutrients. The Mediterranean diet, widely studied for its health benefits, serves as an excellent model. The “how” involves practical steps: meal planning, reading food labels, cooking at home more often, and reducing reliance on ultra-processed foods. Small changes—like swapping sugary drinks for water or adding a serving of vegetables to dinner—can make a meaningful difference over time.

Stress regulation is often overlooked, yet it plays a critical role in long-term health. Chronic stress contributes to high blood pressure, weakened immunity, and hormonal imbalances. The “why” is clear: the body’s stress response, designed for short-term survival, becomes harmful when activated constantly. The “what” includes techniques that activate the parasympathetic nervous system—such as deep breathing, meditation, yoga, or spending time in nature. The “how” is about integration: setting aside five to ten minutes daily for mindfulness, using apps that guide relaxation exercises, or establishing calming evening routines. These practices do not eliminate stress, but they improve the body’s ability to recover from it, preserving both mental and physical well-being.

The Role of Screenings and Professional Guidance

No amount of self-care can replace the value of professional medical guidance. While lifestyle habits form the foundation of prevention, regular health screenings are essential for early detection and risk assessment. These tools provide objective data that personal feelings alone cannot reveal. Blood pressure checks, cholesterol panels, blood glucose tests, and cancer screenings such as Pap smears and colonoscopies are proven methods for identifying silent threats. For women over 40, mammograms can detect breast cancer at a stage when treatment is most effective. For those with a family history of heart disease, an echocardiogram or stress test may offer critical insights.

These screenings are not one-size-fits-all. Recommendations vary based on age, gender, family history, and personal risk factors. This is where healthcare providers play a vital role. A primary care physician can help determine which tests are appropriate and when to begin them. Open communication is key—sharing concerns, lifestyle habits, and family medical history allows for personalized advice. Some women hesitate to discuss health issues, either due to fear or the belief that they are too busy. Yet investing time in preventive care today can prevent far greater demands on time and energy in the future.

Doctors are not just problem-solvers; they are partners in health. They can interpret test results, recommend evidence-based interventions, and connect patients with specialists when needed. They can also help distinguish between reliable information and misinformation, which is increasingly common in the digital age. Rather than relying on social media trends or anecdotal advice, consulting a trusted provider ensures that decisions are grounded in science. Preventive care is not about suspicion or alarm, but about vigilance and responsibility—a shared effort between individual and medical team.

Making Prevention a Lifestyle: Long-Term Thinking in a Fast-Paced World

In a culture that values speed and immediate results, preventive health can feel like a low priority. Many women juggle work, family, and household responsibilities, leaving little time or energy for self-care. The idea of “adding” another task—like exercise or meal planning—can seem overwhelming. Yet prevention is not about adding burdens, but about rethinking priorities. It’s about recognizing that caring for oneself is not selfish, but necessary—for the sake of loved ones and personal fulfillment.

Common barriers include lack of time, motivation, and access to accurate information. The solution lies in simplification and integration. Habit stacking—pairing a new behavior with an existing one—can make adoption easier. For example, doing calf raises while brushing teeth, listening to a wellness podcast during a commute, or preparing healthy snacks while cooking dinner. Environmental design also helps: keeping fruit on the counter, placing walking shoes by the door, or using smaller plates to manage portion sizes. These small changes reduce reliance on willpower and make healthy choices the default.

Social support enhances sustainability. Sharing goals with a friend, joining a walking group, or cooking healthy meals with family creates accountability and enjoyment. Prevention does not have to be solitary or joyless. It can be woven into the fabric of daily life—through shared meals, active outings, or quiet moments of reflection. Viewing health as an investment, rather than an expense, shifts the perspective from sacrifice to empowerment. Just as saving money builds financial security, consistent healthy habits build physical and emotional resilience.

Ultimately, disease prevention is not about living in fear of illness, but about creating freedom—the freedom to move without pain, to think clearly, to enjoy time with family, and to age with dignity. It is about making choices today that allow for a fuller, more vibrant life tomorrow. Science provides the roadmap, but the journey begins with a single step: the decision to care, not when broken, but while still strong.