How I Bounced Back: The Real Power of Moderate Movement in Recovery

Recovery isn’t just about rest—it’s about moving wisely. After my own rehabilitation journey, I learned that moderate exercise isn’t just safe; it’s essential. It reduced stiffness, boosted my mood, and sped up healing. Backed by science and real experience, this is how gentle, consistent motion became my most powerful recovery tool—no gym required. For many women in their 30s to 50s managing recovery from surgery, injury, or chronic conditions, the idea of exercise can feel intimidating, even risky. Yet, the truth is that doing too little can be far more harmful than doing too much—when movement is done right.

The Hidden Problem: Why Inactivity Slows Healing

One of the most persistent myths in recovery is that healing means complete stillness. Many people believe that to protect an injured area, they must avoid using it altogether. While short-term rest is often necessary, prolonged inactivity can actually delay recovery and lead to new complications. Muscles begin to weaken within days of disuse, a process known as muscle atrophy. Joints lose their natural lubrication, increasing stiffness and discomfort. Circulation slows, reducing the delivery of oxygen and nutrients essential for tissue repair. This physical decline is medically referred to as deconditioning—a condition that affects not only the injured area but the entire body.

Research in rehabilitation medicine consistently shows that patients who remain inactive for extended periods often face longer recovery timelines and greater difficulty regaining function. For example, individuals recovering from orthopedic surgeries such as knee or hip replacements who avoid movement early in recovery are more likely to experience joint stiffness, muscle weakness, and reduced mobility. In contrast, those who begin gentle, guided movement soon after surgery tend to regain independence faster and report less pain over time. A study published in the Journal of the American Physical Therapy Association found that early mobilization after surgery reduced hospital stays by an average of two days and lowered the risk of complications such as blood clots and pneumonia.

The consequences of inactivity extend beyond the physical. Emotional well-being is deeply tied to physical function. When movement is restricted for too long, many individuals report feelings of frustration, helplessness, and even depression. The inability to perform simple daily tasks—like walking to the mailbox or climbing stairs—can erode confidence and independence. These emotional setbacks can create a cycle where fear of movement leads to more inactivity, which in turn leads to greater physical decline. Breaking this cycle requires a shift in mindset: from seeing movement as a threat to recognizing it as a vital part of healing.

Real-life examples from rehabilitation centers illustrate this point clearly. One woman in her early 40s, recovering from a back injury, avoided walking for nearly six weeks out of fear that it would worsen her pain. When she finally began working with a physical therapist, she discovered that her lower back stiffness and leg weakness were not due to the original injury but to prolonged immobility. With a structured program of gentle walking and core stabilization exercises, she regained mobility within weeks. Her story is not unique. Countless patients find that their biggest barrier to recovery is not the injury itself, but the belief that rest means doing nothing at all.

Rethinking Recovery: The Science Behind Moderate Exercise

Modern rehabilitation science has redefined what recovery looks like, placing moderate movement at its core. But what exactly counts as “moderate” in the context of healing? Moderate exercise refers to physical activity that raises the heart rate slightly and allows for easy conversation—typically rated as a 3 to 5 on a scale of 10 for effort. This includes activities like walking at a comfortable pace, performing gentle range-of-motion stretches, or participating in water-based exercises. The key is consistency and safety, not intensity. Unlike high-impact workouts designed for fitness, moderate movement in recovery is tailored to support the body’s natural repair processes without causing strain.

Physiologically, movement acts like a delivery system for healing. When muscles contract during activity, they pump blood through surrounding tissues, enhancing circulation. Improved blood flow brings oxygen and essential nutrients to injured areas, accelerating tissue regeneration. At the same time, movement stimulates the production of synovial fluid, the natural lubricant in joints, which helps reduce stiffness and improve mobility. For individuals recovering from joint injuries or surgeries, this lubrication is critical in preventing long-term stiffness and degeneration.

Another important benefit of moderate exercise is its impact on the nervous system. After an injury, the brain often becomes overly protective, interpreting even mild sensations as potential threats. This can lead to muscle guarding, where the body involuntarily tenses muscles around an injured area, limiting movement. Gentle, repetitive motion helps retrain the nervous system, signaling that movement is safe. This process, known as neural reactivation, plays a crucial role in restoring normal function and reducing chronic pain.

The mental and hormonal effects of moderate movement are equally powerful. Physical activity triggers the release of endorphins, the body’s natural painkillers and mood enhancers. These chemicals not only reduce the perception of pain but also promote a sense of well-being. Additionally, regular light exercise has been shown to lower levels of inflammatory markers in the body, which is especially beneficial for those managing conditions like arthritis or fibromyalgia. Improved sleep is another well-documented outcome—patients who engage in daily gentle movement often report falling asleep faster and experiencing deeper, more restorative rest.

Scientific evidence supports these benefits. A 2022 review in the British Journal of Sports Medicine analyzed over 30 clinical trials and concluded that structured, low-intensity exercise programs significantly improved recovery outcomes across a range of conditions, including post-surgical rehabilitation, stroke recovery, and chronic pain management. The most effective programs were those that started early, progressed gradually, and were supervised by trained professionals. These findings reinforce a simple but transformative idea: healing is not passive. The body repairs itself best when gently activated, not isolated.

Breaking the Fear: Overcoming the “I Might Hurt Myself” Mindset

One of the most common emotional barriers to movement during recovery is the fear of causing further harm. This fear, known in medical terms as kinesiophobia, is especially prevalent among women who have experienced significant injuries, surgeries, or chronic pain. The concern is understandable—after all, pain is the body’s warning system. But when fear becomes overwhelming, it can prevent people from taking the very steps needed to heal. The key to overcoming this mindset is understanding that not all movement is dangerous, and that pain does not always mean damage.

Gentle exercise in rehabilitation is specifically designed to stay within safe physiological thresholds. Physical therapists use evidence-based guidelines to prescribe activities that challenge the body just enough to promote healing without exceeding its current capacity. For example, someone recovering from a shoulder injury might begin with pendulum swings—small, gravity-assisted motions that maintain joint mobility without straining healing tissues. These exercises are introduced gradually, with close attention to how the body responds. The goal is not to push through pain, but to expand function in a controlled, sustainable way.

Professional guidance is essential in building confidence. A physical therapist does more than design a program—they serve as an educator, coach, and reassurance provider. They teach patients how to distinguish between normal muscle soreness and harmful pain, how to modify movements based on daily fluctuations in symptoms, and how to track progress over time. This partnership helps replace fear with trust. When patients see that movement leads to improvement—less stiffness, better sleep, increased strength—they begin to view exercise not as a risk, but as a reliable tool for recovery.

Tracking small wins plays a powerful role in shifting mindset. For example, a woman recovering from knee surgery might start by standing at the kitchen counter for one minute without support. A week later, she walks to the end of the driveway. These milestones, though modest, build a sense of accomplishment and reinforce the idea that the body is capable of healing. Over time, this creates a positive feedback loop: movement leads to improvement, which leads to greater confidence, which leads to more movement. Breaking the fear cycle is not about bravery—it’s about having the right support and information to move forward safely.

What Actually Works: Practical Forms of Moderate Exercise in Rehab

When it comes to recovery, the most effective exercises are often the simplest. Walking, for instance, is one of the most widely recommended forms of moderate movement. It requires no special equipment, can be done almost anywhere, and offers a wide range of benefits. For optimal results, experts suggest starting with short durations—just 5 to 10 minutes—and gradually increasing as tolerated. The pace should be comfortable, allowing for easy conversation. Walking on flat, even surfaces reduces joint stress, while arm swing naturally engages the core and improves balance. Over time, increasing distance or adding slight inclines can help build endurance without overloading healing tissues.

Range-of-motion exercises are another cornerstone of rehabilitation. These gentle movements help maintain joint flexibility and prevent stiffness. Examples include shoulder rolls, ankle circles, and neck stretches—each performed slowly and without force. The goal is not to achieve a deep stretch, but to keep joints moving through their natural pathways. These exercises can be done multiple times a day, even while sitting, making them ideal for those with limited mobility or energy. Consistency matters more than intensity; even a few minutes of daily movement can make a significant difference over time.

Water-based activities offer a unique advantage for those managing pain or joint limitations. Aquatic therapy, often conducted in a heated pool, uses water’s buoyancy to reduce the impact on joints while still allowing for resistance and movement. The warmth of the water helps relax muscles and improve circulation, making it particularly beneficial for individuals with arthritis or fibromyalgia. Exercises such as water walking, leg lifts, and gentle arm movements provide a full-body workout with minimal strain. Many rehabilitation centers offer supervised aquatic programs, but even recreational swimming or walking in chest-deep water can be effective when done mindfully.

Mind-body practices like tai chi, qigong, and gentle yoga have also gained recognition in rehabilitation settings. These disciplines combine slow, deliberate movements with focused breathing and mental awareness. They improve balance, coordination, and body awareness—skills that are especially important for older adults or those recovering from neurological conditions. Studies have shown that tai chi, for example, can reduce fall risk in older adults by improving postural control. Gentle yoga has been linked to reduced pain and improved function in individuals with chronic lower back pain. These practices emphasize mindfulness and self-compassion, helping patients reconnect with their bodies in a positive, non-judgmental way.

Building a Sustainable Routine: From Daily Habits to Long-Term Gains

One of the most effective strategies in rehabilitation is the 10-minute rule: commit to just 10 minutes of movement each day. This small, manageable goal removes the pressure of needing to complete a long or intense session. The act of starting is often the hardest part, but once movement begins, many people find they naturally continue beyond the initial time. The key is consistency—doing a little every day is more beneficial than doing a lot once in a while. Over time, as strength and endurance improve, the duration and variety of activity can be gradually increased.

Treating movement like a prescription helps reinforce its importance. Just as one would take medication at the same time each day, scheduling movement into a daily routine increases adherence. Whether it’s a morning walk, an afternoon stretch session, or an evening water exercise class, having a set time makes it more likely to happen. Using a calendar, reminder app, or habit tracker can provide additional motivation. The goal is to shift from viewing exercise as an optional task to seeing it as a necessary part of health maintenance.

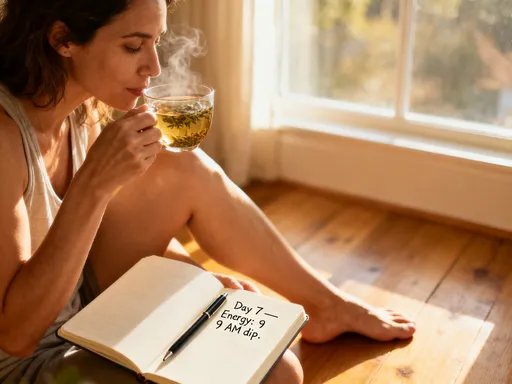

Monitoring symptoms is crucial for long-term success. It’s normal to feel mild muscle soreness after starting a new activity—this is a sign that the body is adapting. However, sharp pain, swelling, or increased fatigue are signals to slow down or modify the activity. Keeping a simple journal to note how the body feels before and after movement can help identify patterns and guide adjustments. For example, if walking in the evening leads to increased stiffness the next morning, switching to a morning session might be more effective. Listening to the body ensures that progress is sustainable and safe.

Integrating movement into daily life removes the need for special equipment or gym memberships. Simple changes—like parking farther from store entrances, taking the stairs instead of the elevator, or standing while talking on the phone—add up over time. Household activities such as gardening, light cleaning, or playing with grandchildren also count as movement. The idea is not to add more to an already full schedule, but to find natural opportunities to stay active throughout the day. This approach makes recovery more accessible and less overwhelming, especially for women balancing family, work, and caregiving responsibilities.

When to Adjust: Listening to Your Body and Knowing Limits

While movement is essential, it’s equally important to recognize when to adjust or pause. Warning signs such as increased pain lasting more than two hours after activity, new swelling, or unusual fatigue indicate that the body needs rest. These signals are not failures—they are valuable feedback. Responding appropriately by reducing intensity, modifying exercises, or taking a day off allows the body to recover and prevents setbacks. Pushing through pain can lead to overuse injuries and prolong the healing process, so honoring the body’s limits is a sign of wisdom, not weakness.

Regular check-ins with healthcare providers ensure that the movement plan remains safe and effective. Physical therapists can assess progress, update exercise programs, and address concerns. Even minor changes—such as a new ache or difficulty sleeping—can provide important clues about how the body is responding. Professional feedback helps fine-tune the approach, ensuring that movement continues to support, rather than hinder, recovery.

Exercise programs should be adapted to individual conditions. For example, someone recovering from a hip replacement may focus on hip flexion exercises and balance training, while a person managing chronic lower back pain might prioritize core stabilization and posture correction. Those with joint issues like osteoarthritis may benefit more from low-impact activities such as swimming or cycling. The principle is universal: the right movement for recovery is the one that matches the body’s current needs and abilities.

Finding the balance between challenge and safety is key. Movement should feel manageable, with room to progress over time. A useful guideline is the “talk test”—if a person can speak comfortably while moving, the intensity is likely appropriate. If speaking becomes difficult, it may be time to slow down. This balance ensures that exercise remains a source of strength and confidence, not strain or fear.

Beyond Recovery: How Moderate Movement Becomes a Lifelong Habit

Recovery is not just about returning to how things were—it’s about building a stronger, more resilient body. As rehabilitation progresses, the focus naturally shifts from healing to maintenance. The habits formed during recovery—daily walking, gentle stretching, mindful movement—become the foundation of long-term health. Women who continue moderate exercise after formal rehab often report higher energy levels, better sleep, and improved mood. They also experience fewer flare-ups of chronic conditions and a reduced risk of future injuries.

The mindset shift is profound. What once felt like a chore—“I have to move”—evolves into a desire—“I want to move.” This change is not about willpower, but about experience. When movement is consistently linked with positive outcomes—less pain, more freedom, greater independence—it becomes inherently rewarding. Over time, it becomes part of identity: not something one does, but who one is.

Health, in this view, is not just the absence of illness, but the presence of vitality. Moderate movement transforms recovery from a temporary phase into a lifelong practice of self-care. It teaches patience, self-awareness, and resilience—qualities that extend far beyond physical healing. Whether it’s a morning walk in the neighborhood, a weekly tai chi class, or daily stretches by the window, these small acts of movement become promises to oneself: to stay active, to stay strong, to keep going.

The body heals not in stillness, but in motion. And the right kind of movement—gentle, consistent, and guided—can change everything. It restores function, rebuilds confidence, and opens the door to a more vibrant, engaged life. For women navigating recovery, the message is clear: you don’t need to do more. You just need to move wisely.