How I Kept My Recovery Going – A Real Talk on Long-Term Rehab Exercises

Recovery doesn’t end after the first few therapy sessions—what you do over months matters most. I learned this the hard way. After an injury, short-term fixes helped, but lasting progress came from consistent, smart movement. This isn’t about quick wins; it’s about building a sustainable exercise routine that supports long-term healing. Let’s explore how small, daily choices can make a real difference in rehabilitation training. While the initial phase of rehab may relieve pain or restore basic function, true recovery unfolds gradually, often beyond the point where most people stop. For many women in their 30s to 50s—balancing family, work, and personal well-being—this long-term commitment can feel overwhelming. Yet, with the right understanding and tools, it becomes not only manageable but empowering.

The Myth of Quick Recovery

Many people believe that once the pain is gone, recovery is complete. This is one of the most common misconceptions in rehabilitation. Pain is only one signal the body sends, and its absence does not mean full healing has occurred. Tissues such as muscles, tendons, ligaments, and even bone require time to regain their strength and resilience. Rushing back to normal activities without proper rebuilding increases the risk of re-injury, sometimes worse than the original condition. For example, someone recovering from a back strain might feel better after a few weeks of therapy but could still have weakened core muscles that leave them vulnerable to future episodes.

True recovery is not a finish line but a continuum. It involves restoring not just physical function but also confidence in movement. When rehabilitation stops prematurely, the body may adapt in ways that lead to long-term imbalances. These compensatory patterns—such as limping, favoring one side, or altering posture—can silently contribute to joint stress and chronic discomfort. Over time, such habits become harder to correct. This is especially relevant for women who may have experienced multiple life changes, including pregnancy, hormonal shifts, or increased sedentary time, all of which affect musculoskeletal health.

Understanding that healing takes time helps shift expectations from immediate results to sustainable progress. The goal is not just to return to where you were before the injury, but to build a stronger, more resilient body than before. This mindset change—from chasing relief to investing in long-term wellness—is the foundation of lasting recovery. It allows individuals to view rehab not as a temporary fix, but as an essential part of health maintenance, much like regular dental care or annual medical checkups.

Why Long-Term Rehab Training Matters

The human body heals in phases, and each stage requires specific types of movement and loading. Immediately after an injury, the focus is on reducing inflammation and protecting the affected area. As healing progresses, tissues need controlled stress to reorganize and strengthen. This process, known as tissue remodeling, can take weeks to months depending on the type and severity of the injury. For instance, tendon healing may require 3 to 6 months of gradual loading to regain full function. Without continued exercise, the tissue may heal in a disorganized way, leading to weakness or stiffness.

Equally important is neuromuscular re-education—the brain’s ability to relearn how to control muscles effectively after an injury. When movement is limited due to pain or immobilization, the neural pathways that coordinate muscle activation can weaken. This is why someone might feel “wobbly” or uncoordinated even after pain has subsided. Long-term rehab exercises help re-establish these connections through repetition and progressive challenges. Studies have shown that patients who continue structured exercise programs for at least three to six months post-injury experience significantly better outcomes, including improved balance, reduced risk of re-injury, and greater confidence in daily activities.

For women managing household responsibilities and caregiving roles, maintaining strength and mobility is not just about recovery—it’s about independence. The ability to lift a child, carry groceries, or stand for long periods while cooking depends on functional strength that must be rebuilt deliberately. Long-term rehab training supports these everyday movements by focusing on core stability, joint mobility, and postural endurance. It’s not about high-intensity workouts but about consistency, precision, and patience. The science is clear: slow, steady progress leads to durable results.

Common Roadblocks in Sustaining Progress

One of the biggest challenges in long-term rehabilitation is maintaining motivation when progress slows or becomes less visible. In the early stages, improvements are often noticeable—less pain, increased range of motion, or the ability to walk farther. But after a few weeks or months, gains may become subtle, leading to frustration or the belief that “nothing is working.” This plateau effect is normal and does not mean the process has stalled. The body is still adapting at a cellular and neurological level, even if changes aren’t obvious.

Another common obstacle is time. Women in midlife often juggle multiple responsibilities—managing a household, supporting children, caring for aging parents, or working full-time. Finding space for daily exercises can feel impossible. Some may also struggle with unclear goals. Without specific, measurable objectives, it’s easy to lose direction. For example, “getting better” is too vague. A more effective goal might be “walking for 30 minutes without back pain” or “lifting a laundry basket without bending the knees incorrectly.”

Fear of re-injury is another significant barrier. After experiencing pain or a setback, some individuals become overly cautious, avoiding movements that are actually safe and beneficial. This fear can lead to deconditioning, where muscles weaken from underuse, ironically increasing the risk of future injury. Addressing these psychological aspects is as important as physical training. Recognizing that discomfort during rehab is not always harmful—and learning to distinguish between normal soreness and dangerous pain—helps build confidence and resilience.

Designing a Sustainable Exercise Program

An effective long-term rehab program follows a logical progression: mobility, stability, strength, and functional movement. Each stage builds on the previous one, ensuring the body is prepared for increased demands. Mobility exercises help restore joint range of motion and reduce stiffness. These may include gentle neck rolls, shoulder circles, or ankle pumps—simple movements that can be done daily, even while sitting. For those recovering from lower back issues, pelvic tilts or knee-to-chest stretches can gently mobilize the spine.

Stability training focuses on improving control around joints, particularly in the core and pelvis. This is crucial for preventing compensatory movements that lead to strain. Exercises like heel slides, bridging, or quadruped arm/leg raises challenge coordination without overloading the body. Resistance bands are excellent tools at this stage—they provide adjustable tension and support proper form. For example, a seated row with a band strengthens the upper back while promoting good posture, a common issue for women who spend long hours at desks or doing household chores.

Strength training gradually reintroduces load to rebuild muscle endurance. Bodyweight exercises like wall push-ups, step-ups, or modified squats are safe starting points. As tolerance improves, light dumbbells or resistance bands can be added. The key is consistency, not intensity. Two sets of 10–12 repetitions, performed every other day, are often sufficient to stimulate improvement without causing fatigue. Functional movements—such as standing from a chair without using hands or carrying a bag while maintaining upright posture—integrate strength and stability into real-life actions.

A well-designed program is also flexible. It should accommodate daily energy levels and physical fluctuations, especially for women experiencing hormonal changes that affect joint laxity or recovery speed. The program should be personalized, ideally developed with input from a physical therapist, and adjusted as progress is made. Writing down the exercises, scheduling them like appointments, and pairing them with daily habits (e.g., doing stretches after brushing teeth) increases adherence.

Tracking Progress Without Obsessing Over Numbers

Progress in rehabilitation is not always reflected in numbers like weight lifted or repetitions completed. For many, the real victories are quieter but more meaningful: being able to play with grandchildren without back pain, standing through a school event without needing to sit, or sleeping through the night without discomfort. These non-scale victories are powerful indicators of improvement and should be celebrated.

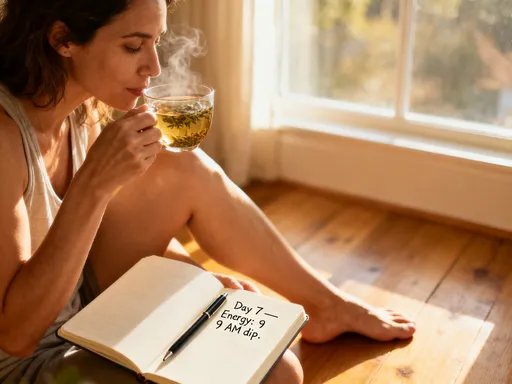

Tracking these changes doesn’t require complex tools. A simple journal can help record daily experiences—how the body feels in the morning, ease of movement during chores, or mood and energy levels. Rating pain or stiffness on a scale of 1 to 10 each week provides a baseline to identify trends. Some find it helpful to take weekly notes like “Today I walked to the mailbox without stopping” or “I carried the laundry basket using proper form.” Over time, these small observations reveal a pattern of progress that might otherwise go unnoticed.

Technology can also support tracking. Smartphone apps that log activity or remind users to move can be useful, but they should not replace self-awareness. The goal is not to achieve a certain step count or workout duration, but to stay connected to the body’s signals. Checking in weekly—asking “Am I moving more easily? Do I feel stronger? Is daily life less taxing?”—helps maintain perspective. This reflective approach fosters patience and reduces the pressure to “perform,” which is especially important for women who may already feel stretched thin by responsibilities.

Integrating Rehab Into Daily Life

Sustainability comes from integration, not isolation. When rehab exercises are treated as a separate, time-consuming task, they are more likely to be skipped. But when they become part of daily routines, consistency improves. The key is to make movement convenient and relevant. For example, calf raises can be done while waiting for the kettle to boil. Shoulder blade squeezes can be performed while watching the evening news. Even standing with proper posture while folding laundry strengthens core awareness.

Another effective strategy is habit stacking—linking a new behavior to an existing one. After brushing teeth in the morning, one might do a set of neck stretches. Before getting into bed, a few minutes of gentle stretching can promote relaxation and joint health. These micro-movements add up over time, contributing to long-term recovery without requiring extra time. For those working from home or spending long hours at a desk, setting a timer to stand, stretch, or walk for two minutes every hour can prevent stiffness and support circulation.

Family involvement can also enhance adherence. Doing seated leg lifts during a child’s homework time or walking around the block together after dinner turns rehab into shared time. This not only supports physical progress but also strengthens emotional bonds. Creating a dedicated space at home—a corner with a mat, resistance bands, and a small stool—makes it easier to stay on track. Visual cues, like a sticky note on the mirror or a calendar with checkmarks, reinforce commitment without judgment.

When to Seek Professional Guidance

While self-directed rehab is valuable, professional guidance remains essential. Physical therapists are trained to assess movement patterns, identify imbalances, and adjust programs based on individual needs. Regular check-ins—every 4 to 6 weeks, or whenever progress stalls—ensure that the program remains safe and effective. These visits are not a sign of failure but a proactive step in long-term care.

There are specific signs that indicate it’s time to consult a healthcare provider. New or increasing pain, especially if it radiates or persists beyond 24 hours after exercise, should not be ignored. A sudden loss of mobility, such as being unable to lift the arm as high as before, may signal an underlying issue. Other red flags include swelling, numbness, or a feeling of instability in a joint. These symptoms do not necessarily mean something is seriously wrong, but they do require evaluation to prevent complications.

Professionals can also help refine technique. Even small errors in form—such as arching the back during a bridge or shrugging the shoulders during a row—can reduce effectiveness and increase injury risk. A therapist can provide real-time feedback and suggest modifications based on body type, injury history, or lifestyle. Additionally, they may introduce advanced tools like biofeedback devices or therapeutic ultrasound if needed, though these are always used as part of a comprehensive plan.

For women navigating perimenopause or menopause, hormonal changes can affect joint health, muscle mass, and recovery speed. A healthcare provider can offer tailored advice, such as adjusting exercise intensity during certain phases of the menstrual cycle or recommending nutritional support for tissue repair. This personalized approach ensures that rehab evolves with the body, not against it.

Rehabilitation is not a sprint; it’s a commitment to long-term care. The real transformation happens not in the clinic, but in the quiet, consistent effort made every day. By embracing patience, staying informed, and honoring your body’s pace, lasting recovery becomes possible. Always remember: your journey is personal—work with professionals, trust the process, and keep moving forward.