Finding Your Center: How I Retrained My Balance and Stabilized My Body

Balance isn’t just for yogis or athletes—it’s a quiet superpower most of us take for granted until it starts slipping. I didn’t notice mine fading until I stumbled more often, felt wobbly on stairs, and lost confidence on uneven sidewalks. Turns out, balance is a skill you can rebuild. This is how I gently adjusted my body, reconnected with stability, and found a stronger sense of physical control—no magic tricks, just consistent, doable shifts. What began as a personal concern turned into a journey of reawakening my body’s natural ability to stay grounded. And the changes I experienced were not just physical, but emotional and mental as well.

The Moment I Realized My Balance Was Off

It happened on a trail I’d walked dozens of times—a gentle forest path I knew like the back of my hand. One moment I was walking steadily, the next I nearly fell, catching myself just in time on a tree trunk. My heart pounded, not from exertion, but from shock. I hadn’t tripped over a root or misstepped on a rock. My foot had simply landed wrong, and my body didn’t correct itself fast enough. That moment unsettled me more than the fall itself. It was the first real sign that something in my body was no longer responding the way it used to.

Looking back, the clues had been there. I’d been grabbing the handrail more often going up the stairs, even when not carrying anything. I felt uneasy standing on one leg to tie my shoe, and I noticed I swayed slightly when waiting in line. These weren’t dramatic red flags, but a quiet accumulation of small instabilities. Like many people, I’d dismissed them as normal signs of aging or fatigue. But the trail incident forced me to confront the truth: my balance was declining, and I needed to do something about it before it compromised my independence.

The emotional toll of losing balance confidence is often overlooked. It’s not just about the risk of falling—it’s about the subtle erosion of freedom. I began hesitating before stepping onto curbs or walking on gravel. I avoided activities I once enjoyed, like hiking or dancing at family gatherings, out of fear of embarrassment or injury. That sense of limitation, of holding back from life, was more frustrating than any physical symptom. I realized that balance wasn’t just a physical skill—it was tied to my sense of safety, autonomy, and joy in movement.

Research supports this experience. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, one in four adults aged 65 and older falls each year, making falls the leading cause of both fatal and nonfatal injuries in this age group. But imbalance doesn’t only affect older adults. Sedentary lifestyles, poor posture, and lack of varied movement can degrade balance at any age. The good news? Balance is not a fixed trait. It’s a dynamic system that can be improved with awareness and practice, even after years of neglect.

What Balance Really Means (It’s Not Just Standing on One Leg)

When most people think of balance, they picture someone standing on one foot or walking a tightrope. But in reality, balance is far more complex and constantly at work, even when we’re standing still. It’s a dynamic process managed by three key systems: vision, the vestibular system in the inner ear, and proprioception—the body’s sense of where it is in space. These systems send continuous signals to the brain, which integrates the information and makes micro-adjustments in muscles and posture to keep us upright and steady.

Visual input helps us orient ourselves in our environment. The vestibular system detects motion, head position, and spatial orientation, allowing us to maintain equilibrium even with our eyes closed. Proprioception, often called the “sixth sense,” comes from receptors in our muscles, tendons, and joints that tell the brain where our limbs are without us having to look. When you reach for a glass of water without staring at your hand, that’s proprioception at work. All three systems must communicate seamlessly for balance to function properly.

Modern life, however, disrupts this delicate balance network. We spend hours staring at screens, limiting the diversity of our visual tracking and reducing head movement. We walk on flat, predictable surfaces like pavement and tile, depriving our feet and ankles of the varied sensory input they need. We sit for long periods, which weakens the muscles involved in postural control. Over time, these habits dull our body’s natural feedback loops, making us more reliant on vision and less attuned to subtle shifts in weight and position.

Another common misconception is that poor balance only affects older adults. While it’s true that balance tends to decline with age due to muscle loss, reduced sensory input, and slower reaction times, the foundation for that decline is often laid decades earlier. Younger adults who lead sedentary lives or lack diverse movement patterns may already be experiencing subtle deficits in balance without realizing it. The good news is that the nervous system is adaptable. With the right stimuli, we can retrain our body’s balance systems at any age, restoring confidence and stability.

Why Modern Bodies Struggle with Stability

The human body evolved to move across varied terrains—grass, sand, hills, and uneven ground. Our ancestors walked barefoot or in minimal footwear, which allowed their feet to receive rich sensory feedback from the environment. Today, most of us spend our days in cushioned shoes on flat floors, drastically reducing the input our feet send to the brain. This lack of stimulation weakens the small muscles in the feet and ankles, which are crucial for maintaining balance. Think of it like wearing gloves all the time—you’d lose sensitivity in your hands. The same principle applies to the feet.

Sedentary behavior is another major contributor to poor balance. When we sit for hours at a time, our postural muscles—especially those in the core, hips, and lower legs—become underused and weak. These muscles are essential for making the small, automatic adjustments that keep us stable. Without regular activation, they lose tone and responsiveness. Studies have shown that prolonged sitting is associated with reduced ankle strength and impaired postural control, both of which directly impact balance.

Our reliance on screens further compounds the problem. Staring at a phone or computer for long periods encourages a fixed head position and limited eye movement, reducing the mobility of the neck and the brain’s ability to process spatial information. This can dull the vestibular system, which relies on head motion to function optimally. Additionally, multitasking while moving—like texting while walking—divides attention and impairs the brain’s ability to focus on balance-related tasks, increasing the risk of missteps.

The lack of varied movement in daily life also plays a role. Most people follow predictable routines: walk on flat sidewalks, climb stairs, sit at a desk. There’s little opportunity to challenge the body with uneven surfaces, changes in direction, or shifts in weight distribution. Without these challenges, the balance system doesn’t get the practice it needs to stay sharp. It’s like a muscle that isn’t used—it weakens over time. The solution isn’t to overhaul your life, but to reintroduce small, natural challenges that reactivate your body’s stability systems.

Small Shifts That Rewired My Body Awareness

I started my balance journey with simple, low-risk changes I could incorporate into my daily routine. The first was going barefoot at home. I began standing on different surfaces—carpet, tile, a yoga mat—while doing everyday tasks like folding laundry or making coffee. The texture differences forced my feet to work harder and sent more sensory information to my brain. At first, I felt unsteady, especially on harder floors, but within a few weeks, I noticed my feet felt stronger and more responsive.

Another easy habit was turning routine moments into mini balance challenges. I started brushing my teeth while standing on one leg. At first, I could barely last 10 seconds without grabbing the sink, but I gradually increased the time. I also practiced closing my eyes during these exercises, which removed visual input and forced my body to rely more on proprioception and the vestibular system. These small challenges felt almost playful, but they were quietly retraining my nervous system.

I used furniture for light support while testing my stability. For example, I’d stand near a sturdy chair and lift one foot off the ground, holding the position for as long as I could. As my confidence grew, I reduced my reliance on touch and eventually performed the exercise without any support. I also practiced turning quickly from side to side while standing, mimicking real-life movements like checking behind me or reaching for something on a high shelf. These dynamic motions improved my ability to adjust my center of gravity smoothly.

Tracking progress was key to staying motivated. I didn’t need fancy equipment—just noticing that I swayed less when standing still or that I could turn more confidently without grabbing a wall was enough. I also paid attention to how I felt during daily activities. Walking on uneven ground became less intimidating, and I no longer hesitated before stepping off a curb. These subtle improvements reinforced the idea that small, consistent efforts could lead to real change.

Movement Practices That Actually Improve Balance

While daily micro-habits helped, I also incorporated structured movement practices that specifically target balance. One of the simplest and most effective was the heel-to-toe walk—walking in a straight line with the heel of one foot touching the toe of the other. I did this down my hallway, using the wall for light support if needed. It looks easy, but it challenges coordination, alignment, and focus. This exercise is so effective that it’s used in clinical settings to assess balance and fall risk.

Tai Chi and gentle yoga became regular parts of my routine. Tai Chi, in particular, emphasizes slow, controlled movements that require constant weight shifting and mental focus. Research has shown that Tai Chi can significantly reduce fall risk in older adults and improve balance in people of all ages. The flowing motions train the body to move with intention and awareness, which translates to better stability in everyday life. Gentle yoga poses like the tree pose or warrior III also strengthened my core and leg muscles while improving my sense of alignment.

Strength plays a critical role in balance, especially in the ankles, core, and glutes. Weak ankle muscles make it harder to correct small shifts in position, while a weak core reduces overall postural control. I added simple strength exercises like calf raises, seated marches, and glute bridges to my routine. These didn’t require equipment or much time—just 10 to 15 minutes a day. Over time, I noticed my legs felt more stable, and I could stand for longer periods without fatigue.

One of the most important lessons I learned was that consistency matters more than intensity. Short, daily sessions were far more effective than occasional long workouts. The nervous system learns through repetition, so doing a few balance exercises every day—like standing on one leg while waiting for the kettle to boil—created lasting change. It wasn’t about pushing myself to the limit; it was about showing up regularly and giving my body the practice it needed.

The Mind-Body Link: How Focus Enhances Stability

One of the most surprising discoveries in my journey was how closely mental focus is tied to physical stability. When I was distracted—thinking about my to-do list or reacting to a notification—I was more likely to lose my balance. Multitasking while moving, even in small ways, divides the brain’s attention and reduces its ability to process balance-related signals. This is why older adults are often advised not to talk and walk at the same time—it increases fall risk.

To counter this, I began practicing mindful walking. Instead of rushing from one place to another, I slowed down and paid attention to the sensation of my feet touching the ground, the shift of weight from heel to toe, and the rhythm of my breath. This simple act of presence not only improved my balance but also reduced stress. Mindfulness helped me tune into my body’s signals and respond more quickly to subtle changes in stability.

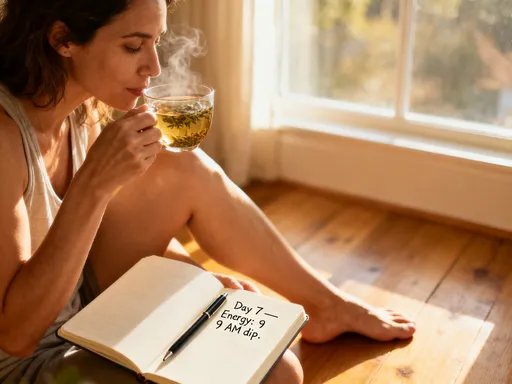

Stress and fatigue also had a noticeable impact on my balance. On days when I was overwhelmed or hadn’t slept well, I felt more unsteady, even if I didn’t consciously notice it. This makes sense from a physiological standpoint: stress activates the sympathetic nervous system, which can impair motor control and coordination. Fatigue slows reaction times and reduces muscle responsiveness. Recognizing this connection helped me prioritize rest and self-care as part of my balance routine.

The deeper I went, the more I saw balance as a reflection of overall well-being. Just as a cluttered mind makes it hard to focus, a stressed or fatigued body struggles to stay steady. By cultivating mental clarity through mindfulness, adequate sleep, and stress management, I supported my physical stability in ways I hadn’t expected. Balance, I realized, wasn’t just a physical skill—it was a state of integration between mind and body.

Making Balance Part of Everyday Life (Not Just “Exercise”)

The most sustainable changes came when I stopped thinking of balance as something to “work on” and started seeing it as a natural part of daily living. I turned chores into opportunities for practice. While loading the dishwasher, I’d stand on one leg. While waiting for the microwave, I’d shift my weight side to side. Reaching for a high shelf became a chance to engage my core and stabilize my stance. These micro-moments added up, reinforcing balance without requiring extra time or effort.

I also created small challenges at work. If I was on a phone call, I’d stand and gently sway from side to side or shift my weight between feet. During meetings, I paid attention to my posture and made subtle adjustments to sit or stand more upright. These habits weren’t about performance—they were about maintaining awareness and keeping my body engaged throughout the day.

The long-term benefits extended beyond stability. My posture improved, my coordination became sharper, and I felt more confident in my movements. I also noticed a reduction in minor aches and pains, likely due to better alignment and muscle engagement. Most importantly, I regained the freedom to move without hesitation. I could walk on a cobblestone street, step off a curb confidently, or dance at a family event without fear.

What I learned is that progress, not perfection, is the goal. There were days when I felt unsteady, and that was okay. The practice wasn’t about achieving flawless balance—it was about building resilience. Each small effort strengthened my body’s ability to adapt and respond. Over time, these adjustments became second nature, woven into the fabric of my daily life.

Stability Starts with Awareness

Looking back, my journey to better balance was about more than physical improvement—it was a reconnection with my body. What began as a concern about stumbling turned into a deeper appreciation for the intricate systems that keep us upright and moving with confidence. I went from feeling hesitant and insecure to standing taller, walking with purpose, and trusting my body again.

Balance is not a destination; it’s an ongoing practice. It requires attention, consistency, and patience. But the rewards are profound: greater independence, reduced injury risk, and a renewed sense of physical mastery. The changes don’t have to be dramatic. Simply standing barefoot, walking mindfully, or doing a few balance exercises each day can make a meaningful difference.

If you’ve noticed your balance slipping, know that it’s never too late to start. Small, consistent adjustments can reawaken your body’s natural stability systems. And if imbalance persists or worsens, it’s important to consult a healthcare provider to rule out underlying conditions. But for most people, the path to better balance begins with awareness—and the willingness to take the first small step.